A Step-by-Step Business Valuation Process Every CFO Should Follow

A Step-by-Step Business Valuation Process Every CFO Should Follow

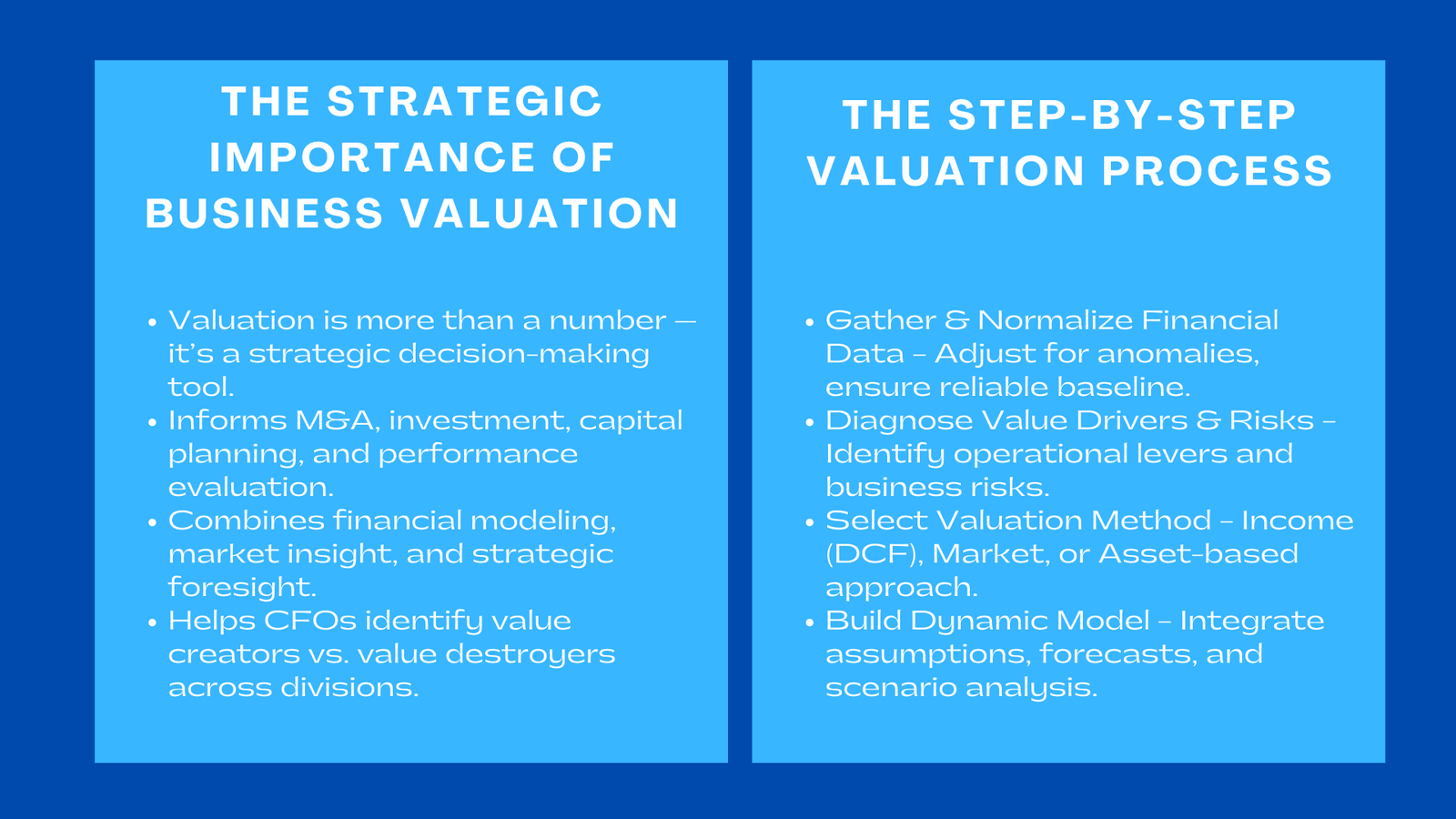

Business valuation is one of the most critical responsibilities in corporate finance and leadership. For CFOs, it goes far beyond simply determining a company’s worth—it is a comprehensive process that informs mergers and acquisitions, investment decisions, capital planning, and even internal performance assessments. A robust valuation reflects not only the company’s current financial position but also its strategic outlook, market competitiveness, and ability to generate sustainable returns.

In today’s dynamic business environment, valuation must balance analytical rigor with contextual judgment. Traditional financial metrics alone are insufficient to capture a company’s real value, especially when intangible assets, market sentiment, and strategic synergies play a growing role. Therefore, the step-by-step business valuation process for CFOs must adopt a structured, step-by-step process that combines accuracy, transparency, and foresight. The goal is not merely to produce a number but to develop a comprehensive understanding of what drives enterprise value and how it can be improved.

The Strategic Role of Valuation in Financial Leadership

Valuation as a Core Strategic Tool

Valuation is the cornerstone of sound financial leadership. When conducted properly, it becomes a decision-making compass that guides everything from corporate acquisitions to pricing strategies and performance targets. For CFOs, valuation is not a periodic exercise performed during a transaction—it is an ongoing framework for evaluating growth, capital efficiency, and shareholder returns, especially when supported by business valuation method Singapore ValueTeam services that ensure accuracy, compliance, and strategic insight.

Through valuation, CFOs can identify which parts of the business are creating or destroying value. This insight enables better capital allocation decisions and provides senior management with an objective foundation for strategic planning. Moreover, embedding valuation thinking across departments—from operations to marketing—encourages a performance-oriented culture where every initiative is evaluated in terms of its contribution to enterprise value.

Defining the Purpose and Context of Valuation

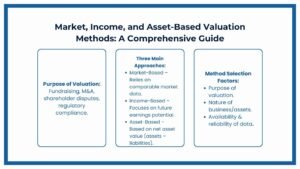

The starting point for every valuation is clarity of purpose. CFOs must define why the valuation is being conducted and who will use its results. Is the goal to raise capital, acquire another business, satisfy regulatory requirements, or simply understand internal performance? Each purpose dictates a different level of rigor, disclosure, and methodology.

For instance, an investor-facing valuation must stand up to due diligence and external scrutiny, requiring defensible assumptions and independent verification. By contrast, an internal valuation conducted for management planning can focus more on scenario modeling and value driver identification. Understanding the valuation’s purpose early ensures that time, effort, and resources are directed efficiently.

Step One: Gathering and Normalizing Financial Data

Establishing the Historical Financial Baseline

The first operational step in a valuation process is the collection of reliable financial data. CFOs must gather audited or reviewed financial statements, including balance sheets, income statements, and cash flow statements from the past three to five years. Supplementary schedules—such as capital expenditure reports, debt breakdowns, and working capital analyses—are equally vital. This historical data provides the foundation upon which all forecasts and valuation models are built.

However, raw data often contains inconsistencies or one-time anomalies that can distort valuation results. Therefore, normalization is necessary to adjust for extraordinary items, accounting irregularities, or owner-specific expenses. The objective is to reveal the company’s sustainable operating performance—a true picture of what the business can consistently earn.

Normalization and Adjustments for Accuracy

Normalization adjustments may include removing non-recurring income, restructuring costs, or personal expenses that inflate or depress earnings. For example, a family-owned company may include discretionary owner compensation that does not reflect market-level salaries. Removing such anomalies ensures comparability with peers and fairness in valuation. Additionally, adjusting for changes in accounting policies, depreciation methods, or lease capitalization enhances accuracy and transparency.

CFOs must document every adjustment made, providing justification for each change. This transparency not only improves the credibility of the valuation but also facilitates external review by auditors, investors, or potential buyers.

Step Two: Diagnosing Business Drivers and Key Risks

Identifying Core Value Drivers

Once financial statements are normalized, the next task is to understand what drives the company’s value. This requires collaboration across departments to map operational performance to financial outcomes. CFOs should examine revenue sources, customer segmentation, cost structures, and capital intensity.

For example, a SaaS (Software as a Service) company’s value may hinge on customer acquisition costs, churn rates, and lifetime value, while a manufacturing company’s key drivers may involve production efficiency and supply chain stability. By identifying these underlying levers, CFOs can quantify the sensitivity of value to changes in operational performance.

Evaluating Internal and External Risk Factors

Alongside value drivers, risks must be carefully assessed. Internal risks include concentration of revenue among a few clients, dependency on key suppliers, or technological obsolescence. External risks may stem from regulatory changes, geopolitical instability, or economic cycles.

CFOs should categorize these risks by likelihood and potential impact, linking them to valuation assumptions. For example, a projected 10% decline in revenue due to regulatory uncertainty should be incorporated into downside scenarios. This structured risk assessment makes the valuation more robust and prepares management for investor scrutiny or negotiation discussions.

Step Three: Selecting the Appropriate Valuation Method

Choosing Among the Three Main Approaches

Valuation methodologies can be broadly categorized into three groups: income-based, market-based, and asset-based approaches. The selection depends on the company’s nature, industry, and purpose of the valuation.

The income approach—typically using the discounted cash flow (DCF) model—estimates value based on expected future cash flows discounted to their present value. It is ideal for companies with predictable financial performance and clear growth trajectories. The market approach benchmarks the company against publicly traded peers or comparable transactions, offering insight into how similar firms are valued in the market. The asset-based approach calculates value based on the fair market value of assets minus liabilities, making it suitable for asset-heavy industries or liquidation scenarios.

Combining Methods for Cross-Verification

CFOs often use multiple methods to cross-validate results. For instance, a DCF analysis might be supported by market multiples derived from comparable companies. If the results diverge significantly, the CFO can review assumptions for potential errors or overly optimistic projections. This triangulation enhances credibility, as it demonstrates that valuation conclusions are supported by multiple analytical lenses.

Step Four: Building the Valuation Model

Constructing a Transparent and Dynamic Model

Once a method is selected, CFOs must ensure that the valuation model is well-structured, transparent, and dynamic. Key inputs—such as growth rates, margins, capital expenditures, and discount rates—should be clearly separated from formulas to facilitate easy adjustments. The model should reconcile across financial statements, linking projected income, balance sheet, and cash flow figures.

Sophisticated CFOs integrate scenario modeling into their valuation spreadsheets. This allows them to test different assumptions, such as changes in market demand, pricing, or operating costs, to see how they affect overall value. A dynamic model not only improves decision-making but also enhances the company’s readiness for investor discussions or audits.

Running Sensitivity and Scenario Analysis

Scenario analysis is a hallmark of a robust valuation. CFOs should prepare base-case, best-case, and worst-case projections, adjusting key assumptions like revenue growth, discount rates, and working capital needs. Sensitivity analysis further identifies which variables most significantly impact the final value. For instance, a 1% change in discount rate or gross margin could alter valuation by millions of dollars.

This exercise provides clarity about risk tolerance and helps executives prioritize strategic actions. It also strengthens the CFO’s ability to communicate valuation uncertainties to stakeholders transparently.

Step Five: Reconciling with Market Evidence

Benchmarking Against Comparable Companies and Transactions

No valuation exists in isolation from the market. Once internal models are complete, CFOs must reconcile findings with external benchmarks. This involves identifying comparable companies (comps) in the same industry, analyzing their financial ratios, and applying valuation multiples such as Enterprise Value/EBITDA or Price/Earnings.

CFOs should adjust these multiples for differences in growth prospects, size, and market conditions. Recent transactions can also provide valuable insight into prevailing valuation trends. If internal results deviate sharply from market benchmarks, it signals the need to revisit assumptions or contextualize differences to stakeholders.

Incorporating Market Perception and Investor Sentiment

Market data often reflects investor sentiment that may not appear in internal models. For instance, high-growth industries like technology may trade at premium multiples due to expectations of future expansion, while cyclical industries may face discounts. CFOs must interpret these dynamics carefully, explaining to stakeholders whether deviations from market averages are justified by unique business strengths or temporary market distortions.

Step Six: Documenting, Presenting, and Defending the Valuation

Preparing a Comprehensive Valuation Report

A professional valuation must be supported by clear documentation. The valuation report should outline the purpose, methodologies used, data sources, assumptions, sensitivity analyses, and any limitations. CFOs should ensure that the report is written in plain, concise language that can be understood by both financial and non-financial stakeholders.

Including visual summaries—charts of cash flow projections, valuation ranges, and risk scenarios—can make complex information more digestible. Thorough documentation not only enhances credibility but also protects the company from disputes or regulatory scrutiny in the future.

Presenting Findings with Confidence

When presenting valuation results to boards, investors, or potential buyers, CFOs should focus on the narrative behind the numbers. It is not enough to display a figure; the CFO must articulate how that value was created, what assumptions support it, and what factors could enhance or erode it. Addressing questions about discount rates, comparable selection, and terminal values with evidence-based reasoning reinforces credibility and builds trust.

Step Seven: Turning Valuation Insights into Strategic Action

From Analysis to Execution

The true value of a valuation lies in how it informs strategy. CFOs should translate the findings into actionable steps: optimizing cost structures, improving capital allocation, or investing in high-growth segments. If valuation analysis reveals that certain product lines or divisions consistently underperform, the company may consider divestiture or restructuring to enhance overall value creation.

Similarly, if scenario testing indicates that working capital is a major driver of valuation sensitivity, CFOs can focus on tightening credit policies or improving inventory turnover. In this way, valuation becomes an ongoing feedback loop between financial analysis and business execution.

Institutionalizing a Valuation Mindset

Forward-thinking organizations treat valuation not as a one-time event but as part of their management culture. By conducting periodic valuations—quarterly, annually, or during major strategic shifts—companies can track how internal decisions and market changes affect enterprise value over time. This continuous approach aligns financial leadership with long-term shareholder interests and prepares the business for unexpected opportunities or challenges.

Step Eight: Ensuring Compliance and Governance

Aligning with Regulatory and Reporting Standards

Valuations often intersect with regulatory frameworks, accounting standards, and audit requirements. CFOs must ensure compliance with international valuation and accounting guidelines such as IFRS, FRS 113 (Fair Value Measurement), or local standards applicable to their jurisdiction. Transparent methodology and consistent disclosure prevent disputes and demonstrate professionalism to auditors, regulators, and investors.

Ethical and Governance Considerations

Integrity is a critical component of valuation. CFOs should maintain independence in the valuation process, avoid manipulation of assumptions for short-term gain, and disclose potential conflicts of interest. Ethical valuation practices protect not only the company’s reputation but also the personal credibility of the financial leadership team.

Conclusion to A Step-by-Step Business Valuation Process Every CFO Should Follow

A well-executed valuation is both a technical and strategic exercise that encapsulates the essence of financial leadership. For CFOs, following a structured, step-by-step process ensures that valuations are accurate, defensible, and insightful. The journey begins with collecting and normalizing data, diagnosing value drivers, selecting appropriate methodologies, and constructing transparent models. It continues how CFOs should conduct company valuations with rigorous testing, market benchmarking, thorough documentation, and strategic implementation of insights.

Ultimately, valuation is not just about determining what a business is worth today—it is about understanding how that worth can grow tomorrow. CFOs who treat valuation as an ongoing strategic discipline, grounded in ethics, analytics, and foresight, will position their organizations to thrive in an increasingly competitive, data-driven, and value-conscious global economy.